By Solana Kline — [A lifelong dog-rescue advocate and avid back-country motorcycle adventure rider]

The early June sunset is throwing rays through the Ponderosas, their boughs waving hello as wind gusts come up off the Mogollon Rim. The pack and I relax on the sandstone, surrounded by the Pondo giants, their warm bark giving off that telltale vanilla-butterscotch aroma that always makes me feel home in Summertime.

This is one of those secret little camp spots where you see more deer and bear than people. Where there’s no cell service. Where you play and rest and remember what it means to be alive and connected to your dog pack and nature’s rhythms.

Betty and Mickey squirrel casually in our temporary back yard. They are on typical camp protocol: the occasional victimless pounce accompanied by vigorous tail-wag, followed by sunshiney horse naps in the dusty sand. I hear them rooting around the scrub oaks next to the rig. I’ve got some delish dinner brewing, which usually perks the pups to attention quicker than anything.

Micks barrels out of the bushes to see what’s cookin’. Betts, usually the snack queen, is slow to follow, stumbling out of the bushes, unable to catch her balance or her footing. I run to her. She is semi-paralyzed and appears not to be reactive or able to see. She’s breathing slowly and inconsistently, she has seizure tremors.

We load up quickly, all possible scenarios running through my head. I kept coming back to rattlesnake bite, what else could it be? I drive like a bat out of hell to the emergency vet in Prescott Valley, watching Betty slowly decline, no longer responding to prompts or verbal calls.

The hour to Yavapai Emergency Vet was excruciating, but we finally made it. They rush Betts in. Shortly after, the vet comes out.

“We think she has THC toxicity. Do you know if she has been exposed to this?”

I was so certain it had been a snakebite that I didn’t even think of cannabis ingestion. I laughed, thinking the vet was joking, picturing Betty sitting down and rolling a big joint to share with Mickey in the bushes. But sure enough, Betty’s toxicology report came back, and she had extremely high levels of THC—the psychoactive component of marijuana. And thank goodness, she was going to be totally fine after the IV fluids and a good night’s sleepers (and maybe a munchie or two).

What the heck? Where would she have picked that up in the middle of the forest? We had spent a lot of time in these zones north of Pine-Strawberry (fun fact: this is the largest stand/network of Ponderosas in the United States), and this had never happened to either of the pups before.

And then, I put two and number-two together: being an ex-street dog, Betty was a notorious human-poo eater, to my constant disgust. My working theory was that Betts had eaten some human feces laden with THC in the woods.

As most of us do these days, I turned to internet sleuthing. Low and behold, I found that pups have exponentially strong reactions to THC expelled via human feces. The reason for this is twofold: 1) We all poo to rid our bodies of things too toxic for our systems to handle, so the THC waste expelled by humans is highly psychoactive and toxic; and, 2) These expelled toxins are especially toxic to dogs due to their own unique toxin processing and neurolandal setup. (Source: https://vcahospitals.com/know-your-pet/marijuana-intoxication-in-dogs-and-cats)

So, theoretically, all it would take is one human getting too high in the forest, popping a squat, and carelessly leaving their scat out in the open for all the four-legged passersby to munch on.

Unfortunately, as many of us have experienced, there’s not much accountability in the disposal of human feces in the forest. While this is already unsettling to see/encounter, it becomes dangerous for our pets and other forest animal friends when the person doing the pooing has ingested drugs and other supplements or pharmaceuticals.

While we all have varying perspectives on the human use of marijuana, I’d venture to guess that most of us don’t want dogs or other animals getting THC toxicity unknowingly. The active component of marijuana is THC, which is highly psychoactive for our doggies and can cause THC intoxication for them. (See https://tinyurl.com/3e6d5ecx)

Symptoms of THC toxicity are neurological and vary greatly in severity, depending on how much is ingested and the size of our pups. Some visible signs of THC exposure and toxicity are tremors, seizures, loss of balance, slow or fast heart rate, drooling, sleepiness or hyperactivity, dilated pupils, slow breathing, disorientation, urinary incontinence, vomiting, and whining.

It should be noted that, just as for humans, cannabis products may be helpful for particular medical conditions—especially cancers and the treatment side-effects. But working with a holistic vet on safe cannabis protocols is key to avoiding toxicity.

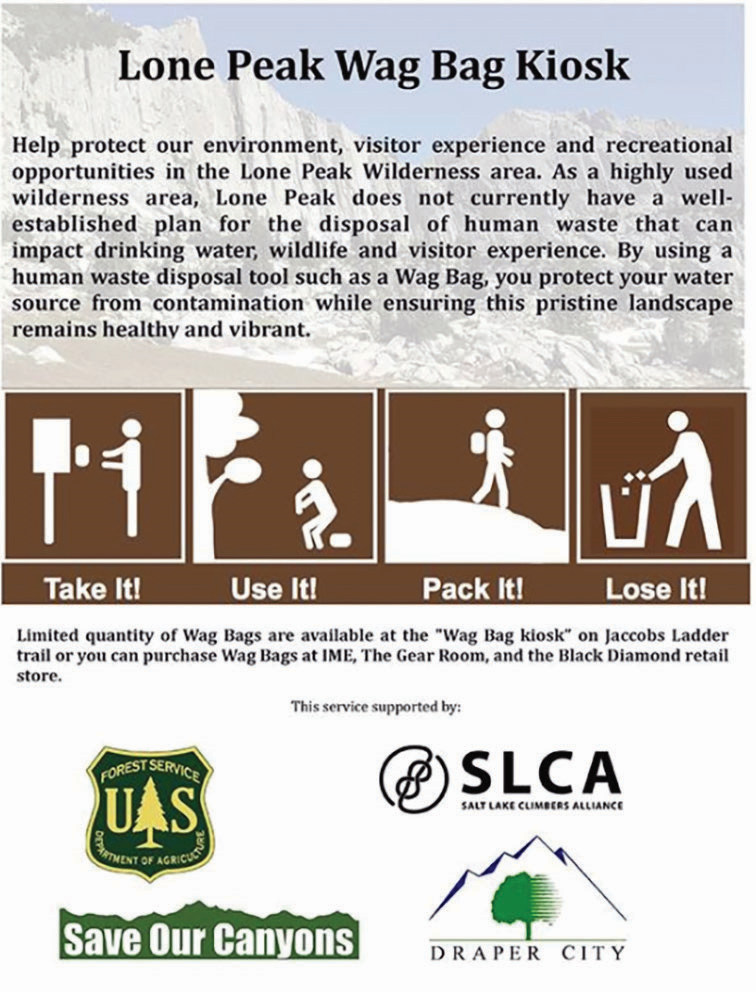

The biggest thing all of us can do with doodie is to be mindful of how we dispose of our number-two’s when we are out in the public lands. Using a WAG bag instead of burying the doodie (https://www.biffybag.com/how-it-works.htm) keeps our pups and other animals from digging it up and eating it as an afternoon snack.

You don’t need a fancy WAG bag: if you’d like to make your own, biodegradable dog-poop bags with some kitty litter work great, and you just pack it out instead of leaving it in camp—easy peasy! This keeps our pets and other animals safe from any supplements or pharmaceuticals we take too, so it’s a win-win! A lot of national recreation sites now have human waste bag dispensers at the trailheads just like we see doggie-poo bag dispensers at parks.

Our pack learned the hard way that the accidental consumption of highly toxic THC compounds in human excrement is no joke. So, whether you are the proud pack leader of a four-legger, a cannabis consumer, or a forest camper, let’s make it our communal responsibility to do our doodie-diligence and pack it out. And tell your four-leggers to scoot around that scat.

Until next time, happy tails and happy trails.

~ Solana and The Pack ~